The 1973 Oil Embargo: The last concerted Arab action

How US policy changed since, what has been learned by all sides and how the legacy of the embargo affected concerted Arab action, unity and perceived strength

A study by Hani M Bathish

The economic and political repercussions and arguable successes or failure of the 1973 oil embargo and what is known as the October War or Yom Kippur War or Six Day War can be boiled down to their essential long lasting impacts nearly 50 years on:

· Arab disunity and collapse of concerted action;

· a change of stance towards Israel by Arab states from a clearly declared enmity to active courtship of the Zionist State, seeking friendship and alliance;

· a Western economic system obsessed with protecting itself against future oil shocks, whether manmade or natural;

· the development of alternative fuels and energy sources (a positive outcome) as well as the cultivation of native sources of crude oil from Texas to the North Sea.

It was, arguably, the greatest humiliation for a world power that resource rich developing countries could work together to deny the United States a vital energy source. A major economic recession resulted from the sudden disruption of crude oil shipments from oil exporting Arab States. The greatest threat, however, to the US was the risk posed by the oil crisis to the cohesion of the North Atlantic Alliance (NATO). Europe took a pro-Arab stance and refused US resupply flights to Israel the right to overfly European territory. It also refused to have any US bases in Europe be used to aid the Israeli war effort. Such a stance seemed unimaginable, as only three decades earlier Europe had been a supporter of Pax Americana, grateful for the US war machine’s help in defeating Nazism.

|

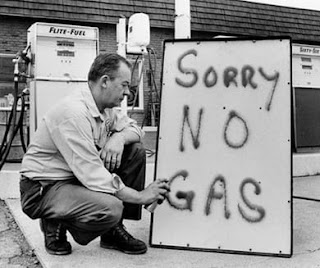

| Once upon a time in America... no gas at the pumps |

By contrast, today, Europe seems to have done a complete about face from its stance 50 years ago, and is meekly courting US favor and desperately trying to avoid US ire, even at the risk of loss of diplomatic face with Iran, Russia and other States and at being seen as the weak sidekick of a domineering dictatorial United States. Even the annexation of most of the West Bank by Israel barely warrants statements of condemnation from the Europeans.

In 1973, the Nixon Administration was faced with a dilemma: its steadfast ally and friend was at war with its Arab neighbors and oil producing Arab States had made good on their threat to cut oil shipments to the US. The administration was forced to start and oversea two sets of negotiations simultaneously (the diplomatic equivalent of fighting a war on two fronts): one between Syria, Egypt and Israel over military disengagement, the other was negotiating with oil producing Arab States (Saudi Arabia, UAE, Kuwait, Qatar, Algeria and Libya) to end the crippling embargo. While the administration tried to discourage any linkage between the two tracks, which it saw as separate, the stronger side, the Arabs arguably, forced the issue regardless. Desperation characterized the Nixon White House as the devastating economic toll of fuel shortages and a 400% rise in oil prices began to bite hard, affecting American, European and first world consumers badly, resulting in increased layoffs and diminished consumer spending.

Was the oil embargo and post oil embargo political landscape an opportunity missed by the Arabs? Could further concerted Arab action have resulted in greater territorial gain, the return of lands lost in the 1967 war including East Jerusalem, the declared sacred cause of the Arabs at the time? Could the Arabs have then gone to the table united as one delegation to talk peace with a severely weakened and isolated Israel? Was it an opportunity for greater Arab diplomatic and political ascendency regionally and globally that was foolishly wasted? Or was the failure of Egyptian and Syrian arms the primary reason for the failure of the oil embargo to achieve any lasting positive results?

Brief Summary

On October 6, 1973, Egypt attacked the Bar Lev Line in the Sinai Peninsula and Syria launched an offensive in the Golan Heights simultaneously. Both territories had been occupied by Israel during the 1967 Six-Day War. On October 12, 1973, US president Richard Nixon authorized Operation Nickel Grass, a strategic airlift to deliver weapons and supplies to Israel in order to replace its losses, after the Soviet Union began sending arms to Syria and Egypt. On October 17, Arab oil producers cut production by 5% and instituted an oil embargo against Israel's allies: The United States, the Netherlands, Rhodesia, South Africa, and Portugal. Saudi Arabia only consented to the embargo after Nixon promised Israel a $2.2 billion military aid package. The embargo was accompanied by gradual monthly production cuts. By December, production had been cut to 25% from September levels. This contributed to a global recession and increased tensions between the United States and its European allies, who faulted the US for provoking an embargo by providing assistance to Israel. (Almost 50 years later, the tables are turned, as several regional countries under US sanctions are blamed for provoking US punitive measures by providing assistance to anti-Zionist resistance movements.)At the time, OAPEC (the Organization of Arab Petroleum Exporting Countries) demanded a complete Israeli withdrawal from all territories beyond the 1949 Armistice border in return for ending the embargo. No Arab organization has had that kind of barefaced confidence since, nor any Arab regime that kind of power to potentially affect the course of regional and international events.

In that solitary, joint, concerted Arab political/military action lay the castration of the US-led world order, if only temporarily. The US was wobbling and losing its footing. The events of 1973 revealed US unpreparedness to deal effectively with a drastic and sudden reduction in the oil supply. The American industrial juggernaut had revealed its Achilles heel. It was a daring Arab move to mobilize Arab oil policy in support of Arab military action and combine the two in order to pose a credible challenge to the reigning Western power of the day and the main sponsor of Israel. It also united the industrialized world, galvanized efforts to find alternative fuels and cheaper or more native sources of crude oil, it forced the automobile industry to respond to consumer demand for smaller more fuel-efficient cars. The days of plentiful cheap oil were over and the psychological impact on American self-perception cannot be ignored or understated. It also awakened the US political community to their glaring vulnerability to foreign oil and the need to have a similarly effective economic coercive weapon at their disposal in order to respond to such embargos effectively.

Impact on the US Economy

American consumers, long used to the freedom that the car had given them, were now standing in line at the pump and restricted to 55 miles per hours on the interstates highways instead of 70mph, a move by the state to reduce fuel consumption by reducing the speed limit. It meant consumers looked to smaller more fuel-efficient cars from abroad, it also meant American car makers inevitably tried their hand at making small cars, most early attempts were dismal failures, such as AMC’s Gremlin. The US and the industrialized world also launched a search for alternative fuels and energy sources to replace oil. Disappearing where the long and wide, lumbering, land-yacht-like gas-guzzlers in favor of smaller four door sedans and hatchbacks from Europe and Japan.

King Faisal’s Statement on relations with and the supply of oil to the US:

“King Faisal of Saudi Arabia, in a television‐interview statement released yesterday, warned the United States that its “complete support of Zionism against the Arabs” would make it “extremely difficult" for his country to continue supplying petroleum to this country.

“We are deeply concerned,” the King said, “that if the United States does not change its policy in the Middle East and continues to side with Zionism, then, I am afraid, such course of action will affect our relations with our American friends because it will place us in an untenable position in the Arab world and vis‐a‐vis the countries which Zionism seeks to destroy.””

August 31, 1973, New York Times

|

| The shoe was once on the other foot! |

The onset of the embargo contributed to an upward spiral in oil prices with global implications. The price of oil per barrel first doubled, then quadrupled, imposing skyrocketing costs on consumers and structural challenges to the stability of whole national economies. Since the embargo coincided with a devaluation of the dollar, a global recession seemed imminent. US allies in Europe and Japan had stockpiled oil supplies, and thereby secured for themselves a short-term cushion, but the long-term possibility of high oil prices and recession precipitated a rift within the Atlantic Alliance. European nations and Japan found themselves in the uncomfortable position of needing US assistance to secure energy sources, even as they sought to disassociate themselves from US Middle East policy. The United States, which faced a growing dependence on oil consumption and dwindling domestic reserves, found itself more reliant on imported oil than ever before, having to negotiate an end to the embargo under harsh domestic economic circumstances that served to diminish its international leverage. To complicate matters, the embargo’s organizers linked its end to successful US efforts to bring about peace between Israel and its Arab neighbors. That peace was a disengagement of forces agreement on the Syrian front and another on the Egyptian from that culminated in the Camp David Accords that resulted in Egypt being the first country to normalize relations with Israel, for which it was vilified by Arab peoples and governments, which led to suspension of its membership in the Arab League.

But before the hasty end of the oil embargo in March 1974, the use of such a powerful policy weapon by the Arabs, proved, at least in the short-term, the efficacy of denying vital energy resources to major modern industrial economies. It was a coercive bloodless weapon that proved more devastating and instantaneous in its impact than many US-imposed sanctions are today. It gave oil producing Arab countries a powerful mechanism at their disposal and a seat at the table.

Yet, the actual benefits accrued to the Arabs from using such a weapon were very few to negligible: a negotiated end to hostilities, UN Peace Keepers stationed to separate combatants, and a new negotiated temporary border that has quickly been made permanent by Israel at least in the Golan Heights. Nothing was actually resolved. No serious peace initiative was launched to address Palestinian rights of return, no major territorial concessions were made by Israel, lands lost by the Arabs in 1967 were not returned, nor was East Jerusalem. It almost seemed like the Arab negotiators were wary of reducing US influence too much lest the Soviets gain further influence and power in the region at America’s expense. It could also be that Gulf Arab countries’ national interests, separate from those of Egypt or Syria or Iraq, lay at some future date in some form of closer military or economic alliance with the United States.

Iran up till then was still a major US friend, but it was also a major competitor for political and military dominance in the Persian Gulf. Several Arab States also eyed the wealthy Gulf Arab monarchies covetously. These Gulf monarchies needed to retain some US goodwill just in case they needed urgent military assistance to protect and prop up their shaky thrones or repel invaders, as they indeed had to in 1991.

The legacy of the oil embargo and a weak/fragmented Arab negotiating side, can be seen today in the many benefits accrued to the United States and Israel who are today feted as protectors and saviors of the Gulf Arab and Sunni cause, from Yemen to Tareeq Jdeedeh, and from Manama to Hasakeh and Kaframbel! Europe too has bolstered the US/Israel anti-Iran alliance by declaring Hezbollah, both military and political wing, a terrorist organization. Not even the IRA was so labeled, as Sinn Fein, the political arm of the IRA, continued to operate and gained a seat at the table and helped negotiate a way out of endless conflict that culminated in the Good Friday Agreement.

The Americans and Israel both learned from the 1973 oil embargo and October War, they spotted a chink in the opposition’s armor, a latent Arab disunity that lay well hidden behind the public statements of support for the Palestinian cause. They exploited this disunity beautifully! Books could and indeed may well be written about this skillful manipulation by the United States of Arab disunity to pit one half of the Arab world against the other.

They say failure teaches you more than success, in the case of the oil embargo it was true, and the systematic dismantling of the Arab Anti-Israel alliance over the past five decades by whatever means were at hand and the enormous success achieved to date is clear evidence of a US-Israel alliance that learned from its failures.

Hard Lesson

A few things to note about the embargo: The US economy shrunk by approximately 2.5 percent, unemployment increased and inflation rose, which resulted in an extended economic recession from 73 thru to 75. There was also an enormous transfer of wealth to Arab Gulf oil producing nationswhich created a new challenge to US hegemony in the region.

Every US president since Richard Nixon has been committed, at least rhetorically, to energy independence. And except for Iran’s notable threats to close the Straits of Hormuz, the ‘oil weapon’ has remained unsheathed.

Back in 2013 the United States was poised to become the world’s number one producer of oil and gas, on its way to achieving more than 90 percent energy self-sufficiency. The US has enormous coal resources and has made strides in promoting efficiency and renewable energy, according to the Center for Strategic and International Studies (CSIS). Then, in 2016, America got a coal-friendly America-first president in Donald Trump which only further focuses the country on energy independence. This would not have happened had the oil shock of 73 not taken place.

And yet, according to the CSIS “a handful of enormous resource holders, mostly in the Middle East, still matter - a lot” As such, the US has had and continues to have a vested interest in courting and coopting regimes in the region who are in charge of these “enormous resources.” The hard lessons learned focused the energies of ever successive President since Nixon on the twin policy of energy independence and keeping Gulf Arab countries closely aligned to US interests and happy!

From the 1980s on

Several things happened in the later part of the 1970s that followed directly from the oil crisis in 1973 and the October War:

· In 1975, the Lebanese Civil War ignited with the ‘fuel’ of armed Palestinian presence and the ‘spark’ of Christian militant hostility towards all Palestinian presence in Lebanon. It’s end result was the exile of the PLO from the Levant entirely and the invasion and occupation of Beirut and most of Lebanese territory by Israel. For the first time since their creation the PLO lost direct land access to their homeland and any possibility of carrying out land operations against Israel. This was followed by Syrian troops entering Lebanon to join their right-wing militia allies in destroying what was left of the armed Palestinian presence that had long been supported by Egypt and had been a thorn in Syria’s side. The eviction of the PLO and ending its presence within what Syria considered its ‘sphere of influence’, was a particular boon to Israel that could breathe a sigh of relief and feel secure behind the South-Lebanon-Army-managed buffer zone in the South.

· The split between the Egyptian and Syrian political tracks, which began with the defeat of October 73 (to some a victory) was made solid and undeniable open enmity when Sadat made his first unannounced visit to Tel Aviv and addressed the Israeli Knesset with a plea for peace. The Arab line had split and had begun to fight among itself! The signing of the Camp David Peace accords, which could be argued ultimately led to Sadat’s assassination, was the culmination of what the Syrians and most Arabs at the time saw as a betrayal. The temptations dangled before Egypt by the Americans and the Israelis must have been enormous and too good to pass up. Egypt did what Egypt thought was in its best interest and therein lies the Arab dilemma: separate selfish peace settlements that favor the enemy. All hope of concerted Arab action ended then as the Arabs effectively split between a pro-Western faction eager for a US sponsored peace at almost any price, and the anti-Western faction still hopeful of greater and more direct Soviet intervention to achieve the much-vaunted total liberation of Palestine that began to sound more and more unrealistic with every passing betrayal. Liberation by proxy was never going to be a realistic vision for any politically mature nation.

Thus, by the election of Ronald Reagan, the 40thpresident of the United States, the die had been cast and any immediate threat to Israel had been severely blunted if not annihilated.

Before the 1980s, Iran had fallen to the chaos of revolution, but a new number one US ally was emerging in the form of Saudi Arabia. In 1979, the Soviets invaded Afghanistan, the same bottomless pit of misery that had once challenged and confounded British imperial military might at its height. As time went by, this war would sap Soviet military strength and deplete its treasure, which meant the Soviets were less capable of helping the Arabs ‘liberate’ Palestine or even pay the Arabs the same attention they had paid them before.

The Islamic Revolution in Iran was another blow to US prestige, in particular the overrunning and occupation of the US Embassy in Teheran and holding many US diplomats hostage by Iranian revolutionaries. The revolution was also an opportunity for the US to test its new sanctions weapon. In response to the detention of US diplomats, President Carter issued executive order 12170 in November 1979 freezing Iranian State assets including bank deposits, gold and other properties worth $12 billion at the time. Iran argues that $10 billion remains frozen in the US to this day. This was a new face of American power.

The Iranian Revolution forced America to accept a new ‘primary’ ally in the region that would keep the Arab Gulf monarchies in line and prevent any move to impose a future oil embargos or take any aggressive stance directed at Israel: and that ally was the Kingdom of Saudi Arabia.

The US policy makers knew that the key to thwarting any future military campaign against Israel was to be in control of Arab funds and the Arab treasury. Already, the successors of King Faisal had built a stronger relationship with the US and adopted a stance more aligned with US interests in the region than with those of the other Arab States. Now the full undivided attention of US foreign policy efforts was directed to building stronger ties with the Gulf monarchies, once seen as British turf.

Since then, US general policy in the region in dealing with any challengers has been: tempt with the carrot, but keep the stick within easy reach.

Economic and political coercion as a policy tool

In an article penned in 1974 by Hartmut Brosche in the Journal of International Law of Case Western Reserve University, we note the beginnings of economic and political coercion as a retaliatory option proposed to the Nixon administration by highly placed State officials. The concept of denying US aid and exports to countries that deny vital raw materials to the US was a new idea, it was proposed as a tool placed at the disposal and discretion of the US President. In this proposal, we see the beginnings of the slippery path that has led the US to use economic coercion and sanctions as a form of ‘lazy diplomacy’ to get what it wants from other countries by other than force of arms or the threat of use of force.

Prof. Richard Gardner, Assistant Secretary of State for International Affairs under Kennedy and member of Nixon’s commission on international trade and investment policy, proposed to deny US exports and aid to countries which refuse to supply the US and other States with raw materials. His speech given on November 14, 1973 before 2,000 business leaders at the 60th National Foreign Trade Convention stimulated many US Senators to ask for major changes in President Nixon's trade legislation. The professor asked for language in the legislation that would allow the President to deny exports and aid to those countries that deny the US and other States access to vital raw materials such as crude oil.

The professor stressed that he was not proposing "at this time" that the United States retaliate against the Arab oil-producing countries because there was still a chance that a Middle East settlement might be achieved through quiet diplomacy. However, he said that the US negotiating position would be strengthened "by some carefully drawn amendments to the trade bill that put the oil producing nations and others on notice that they cannot wage economic war on the US with impunity.” He noted that although the US needed Arab oil, the Arabs depend on the US and its partners for food, medicine and industrial machinery, as well as consumer goods, and the Soviets weren’t in a positon to fill that gap completely.

Thus, in this article, we see the basic outlines of a new kind of pressure war, one that does not require large armies to mobilize and invade other countries’ territories, since that is expressly prohibited by the UN Charter, Article 2 (4) which “prohibits the threat or use of force and calls on all Members to respect the sovereignty, territorial integrity and political independence of other States.”

It was recognized then that the future of international relations, beyond the polite dance of diplomacy, lay in waging wars of an economic nature, the primary tool of which would be denial of supplies, whether of raw materials or food or medicine or other vital consumer goods or machinery or spare parts.

We see that today the US has become a master practitioner of the new economic pressure war tactic, imposing harsh sanctions on countries that include: Russia, North Korea, Iran, Venezuela, Syria and to a lesser degree trade restrictions on China, and financial limitations on Lebanon. The problem with economic wars is that they can stretch out without limit or end if the country imposing this kind of sanction is economically stronger than the countries it targets for sanctions. The resulting privations and suffering isn’t felt by the ruling classes or the military of these sanctioned countries, but by their people, who are even used at times to place pressure on their own government to push it to acquiesce to American economic and financial pressure.

Professor Gardner encouraged the development of multilateral sanctions that could be imposed on countries that deny equal access to vital resources. He urged new rules to international law be written to provide for equal access to raw materials and the imposition of multilateral trade and aid embargoes on countries that withhold vital raw materials for political purposes “just as air service is cut to countries that harbor hijackers, or port facilities are denied to countries that pollute the oceans with their tankers.”

This was by no means new, however. Financial and economic pressure had been imposed on Chile, a tactic that resulted in the violent overthrow of an elected President of that country. But the oil embargo by Arab oil producing States differed in that it was developing countries that waged economic war on developed countries for political reasons, whereas in Chile, only two countries were involved, Chile and the US, and the US used international organizations such as the World Bank and the Inter-America Development Bank to force the outcome in its favor in Chile.

In the case of oil, in 1973, the vast majority of global oil reserves lay under the sands of the Middle East. Saudi Arabia and other Arab oil exporters had at their disposal a significant weapon, a weapon King Faisal was always reluctant to use, stating that “oil and politics do not mix”. Even the US was dismissive up until 1973 of the possibility that the Arabs could impose and sustain an effective oil embargo. They would say that “the Arabs need us as much as we need them”, or “they can’t drink the oil”, or “boycotts never work”.

There were, however, several factors that changed in the run up to the Yom Kippur War and the Oil Embargo: the floating of the US Dollar that was no longer pegged to the gold standard meant that Arab oil that was paid for in dollars was now worth a lot less; pressure also built within OPEC to take a stronger line with international oil companies that controlled the trade in the commodity, most of which were American; added to which, anti-American hostility within the Arab world was growing due to continued US support of Israel. In May, President Anwar Sadat called on Arab States to pressure the US to drop its support of Israel. On May 15, Libya, Iraq, Kuwait and Algeria temporality halted the flow of oil to the West as a protest over the continued existence of Israel as a State.

In the aforementioned New York Times article, the world could see that even King Faisal was now shifting from the stance of a man determined not to mix oil and politics to one warning the US that it would become increasingly difficult to prevent oil from being so used.

Sudden and shocking, was therefore the impact of the oil embargo. The US doubted the Arab resolve to use oil as a weapon, but, the Arabs did still more, they raised the price of oil abandoning the established pricing structure.

Secretary of State Kissinger in November 1973 said the US might consider “retaliatory action” if the embargo continued “unreasonably and indefinitely”, like much of US sanctions today. Dr. Kissinger’s position seems to have been barefaced arrogance and the pot calling the kettle black! To which the Saudi Oil Minister Yamani responded by warning that if the US uses military force to restore oil flow, the Kingdom would “blow up its oil fields”.

But, by the end of March 1974, the oil embargo was lifted. Egypt managed to get Israel to pull back its forces from areas West of the Suez Canal and the UN created buffer zones between Egyptian and Israeli forces. In Syria, Kissinger managed to hammer out a disengagement agreement between the Syrians and Israelis by May 31 when the guns finally fell silent.

But, the question to ask is what benefit has the cause of the liberation of Palestine derived from the war, embargo and disengagement agreements, a cause for which many Arab soldiers from many Arab countries had fought and died for?

The answer: Nothing. In fact, the premature and limited use of oil as a weapon has done the cause more harm than good.

Today, we see the legacy of economic pressure tactics of the early 1970s. The broad and ill-considered use of multilateral and even unilateral sanctions by the US and its allies as a preferred weapon to compel change in behavior by perceived errant State, has seen the systematic dismantling of the global free trade system that the very same allies were determined to institute and protect at the end of the Second World War.

Today, weaker States, or those with conflicting interests to those of the US, or those struggling to extract justice from allies of the US, find the Sword of Damocles of US sanctions hanging over their heads like a dark foreboding shadow. The sovereignty of States is now a doubtful concept, since no State is free from potential US economic and financial coercive action should the politics of that State not suit US interests.

Powerful countries that were once widely seen as undemocratic and politically repressive with unpleasant regimes in charge, are today looked at by some beleaguered countries as potential allies and saviors in an economic and financial war waged by the US against them with no limit and no end in sight, simply for daring to challenge US dictates.

Conclusion

Fifty years on from the first major oil shock and the world is far less secure, more anxious and is a more dangerous place. Today, US sanctions policy has continued to stunt the Iranian economy and increase privations on the poorest Iranians, they even risked lives by preventing essential COVID 19 medical supplies from getting into the country. Arguably, the longest standing US sanctions are those placed on Cuba, which began with a physical naval blockade of the island, but was eased considerably under the Obama Administration, but still continues to impact economic growth and prospects for young people in Cuba who are denied opportunities their American counterparts take for granted, all for an argument that’s over half a century old!

The Cuban sanctions are sustained by an anti-Cuban-regime émigré community in the US with political lobbying muscle. Sanctions against Iran’s revolutionary regime have similarly lasted for a long time, over 40 years to date. But, none of these regimes have collapsed or been toppled by pro-Western political forces from within the sanctioned country. Iraq, a country sanctioned by the US after 1991 showed regime robustness and resilience to the worst impacts of the sanctions. In fact, regime collapse in Iraq was only achieved by direct US military intervention, an intervention that many in the West were opposed to.

If the weapon of economic coercion shows anything it is that developing non-industrial countries with weak democratic systems display greater resilience to such sanctions, unlike developed industrial countries whose vibrant economies are highly sensitive to any kind of shock, sanction or embargo, especially restriction of vital resources and raw materials. The overuse of economic pressure tactics by the US has also turned global public opinion against the US and its policies.

International forums like the UN have proved to be unwilling or unable to confront unilateral US economic coercive measures that seriously impact the economic futures of many countries, which leaves those countries that fall victim to the sanctions regime without recourse except continued confrontation and challenge to US interests. Coercive economic measures resolve nothing.

Comments

Post a Comment